Near a quiet bend of the Patoyacu River in Peru’s northern Amazon, 25-year-old Wilmer Macusi, an Indigenous Urarina leader, stood atop a rusty pipeline that cuts through the jungle. He swirled a branch in the stagnant water pooled around it.

“They say this is clean,” Macusi said, pointing to the water where an oil spill occurred in early 2023. “But if you move it, oil still comes out.”

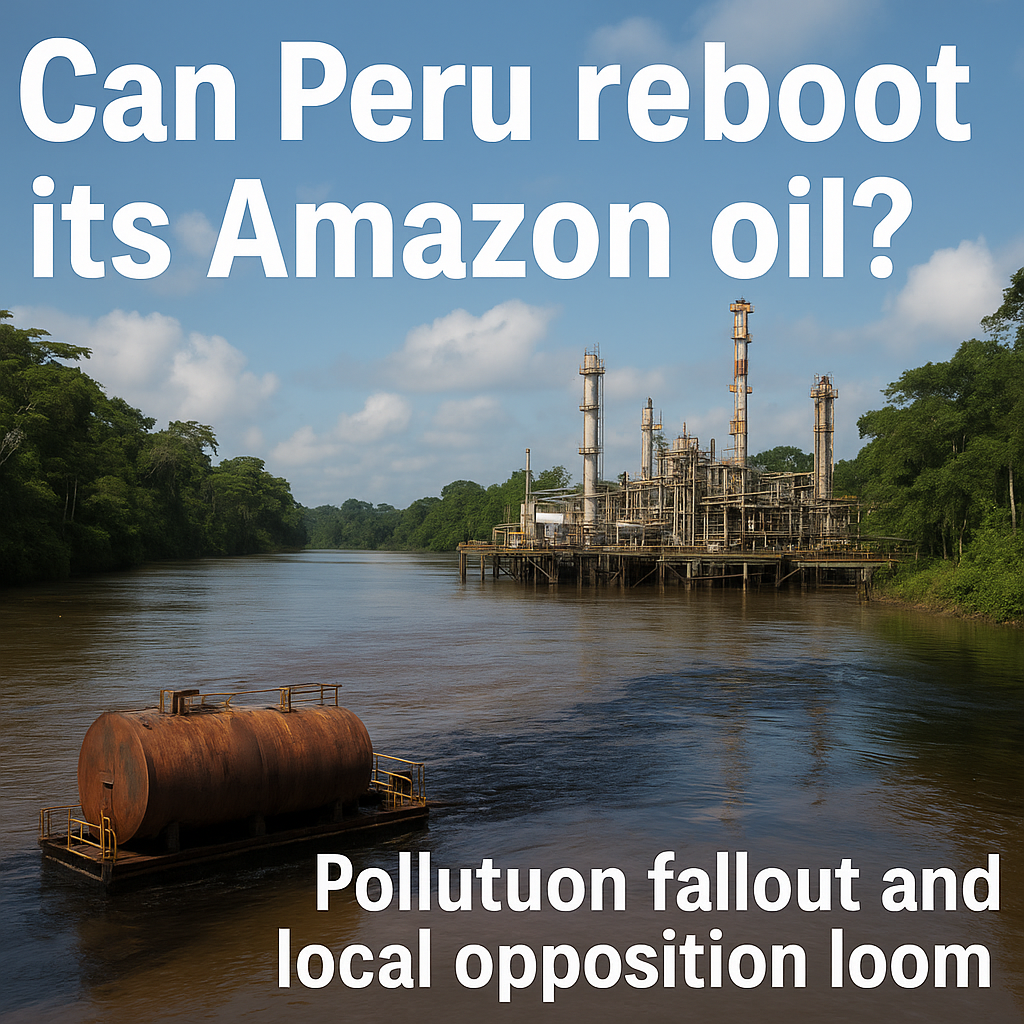

Black droplets bubbled up, defying the plastic barriers meant to contain the spill. This pipeline links the nearby Block 8 oilfield to the government-owned North Peruvian Pipeline (ONP), passing just a short walk from Macusi’s community of Santa Rosa.

Peru’s northern Amazon holds hundreds of millions of barrels of crude, yet Indigenous communities argue that decades of oil extraction brought pollution rather than progress. The region, which once produced over 200,000 barrels per day in the 1980s, now struggles with less than 40,000 bpd after environmental damage and local opposition left key blocks dormant in 2020.

Despite this, Petroperu, the state oil company, is eager to revive production. Having invested $6.5 billion to upgrade its Talara refinery, Petroperu aims to export high-grade fuels. The company estimates the region’s proven reserves at $20.9 billion, potentially generating $3.1 billion in local tax revenues.

Yet past oil spills and environmental damage have sparked mistrust. Indigenous groups, already frustrated by inadequate climate action, staged protests at COP30, clashing with security guards. Petroperu also plans to import oil via Ecuador, which is expanding its own Amazon operations. But pipeline expansions face strong resistance from Indigenous communities in both countries.

Efforts to revive major oilfields face hurdles. Block 192, which once produced over 100,000 bpd, remains contentious due to protests demanding forest, soil, and water remediation. Petroperu’s partnership with Upland Oil & Gas has brought training and jobs to communities, but responsibility for past spills remains unresolved.

Decades of research reveal alarming levels of lead, mercury, cadmium, and arsenic in wildlife and local residents. Estimated cleanup costs for just Block 192 reach $1.5 billion. Indigenous leaders like Macusi remain cautious.

“If the promised benefits don’t come soon, we’ll take measures,” Macusi says, reflecting the patience and resilience of communities who have lived with oil contamination for generations.

This story underscores a broader tension: balancing economic development with environmental responsibility and Indigenous rights. Peru’s Amazon is not just a frontier of crude oil—it is home to communities fighting to protect their land and future.